I was working on a feature last Tuesday night—just a simple data fetcher for a dashboard—when TypeScript decided to gaslight me. The compiler was happy. The linter was silent. My types were “perfect.”

But every time I ran the code? Crash. Cannot read properties of undefined (reading 'map').

I stared at the interface definition for ten minutes. I knew the data structure was correct. I’d written it myself. But here’s the thing about TypeScript that we often forget in the heat of the moment: Types are compile-time fiction. Runtime is the messy reality.

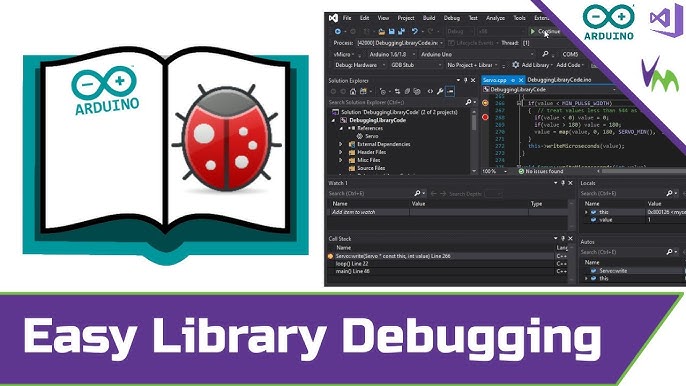

If you’ve been relying solely on console.log to debug TypeScript, you’re playing on hard mode. I used to do it too. “It’s faster,” I told myself. It’s not. It’s just familiar.

The Source Map disconnect

First off, if you aren’t generating source maps, you aren’t debugging TypeScript; you’re debugging compiled JavaScript while trying to mentally reverse-engineer it back to your source code. It’s masochism.

I’ve jumped into so many codebases where tsconfig.json was missing this one line. It drives me up the wall.

{

"compilerOptions": {

"target": "es2022",

"module": "commonjs",

"sourceMap": true, // <-- Please, for the love of sanity

"outDir": "./dist",

"strict": true,

"esModuleInterop": true

}

}Without sourceMap: true, your breakpoints in VS Code (or Chrome DevTools) will jump around unpredictably because the lines don’t match up. You place a break on line 42, and the debugger pauses on line 58. It’s disorienting.

Stop using console.log for Async flows

Async code is where console.log falls apart. By the time you see the log, the state might have mutated three more times. I ran into this specifically with a user data fetcher recently. The API was returning a 200 OK, but the data shape wasn’t what my interface expected.

Here is the setup I actually use in VS Code. Create a .vscode/launch.json file. Don’t be intimidated by the config; you only need to set it up once.

{

"version": "0.2.0",

"configurations": [

{

"type": "node",

"request": "launch",

"name": "Debug Current TS File",

"program": "${file}",

"preLaunchTask": "tsc: build - tsconfig.json",

"outFiles": ["${workspaceFolder}/dist/**/*.js"],

"skipFiles": ["<node_internals>/**"]

}

]

}Now, let’s look at the actual code that broke. This is a pattern I see everywhere—trusting the backend too much.

interface User {

id: number;

name: string;

roles: string[];

}

// The "Trust Me Bro" approach

async function fetchUserData(userId: number): Promise<User> {

// We assume this returns exactly what the interface says

const response = await fetch(https://api.example.com/users/${userId});

const data = await response.json();

// TypeScript is happy here.

// Runtime is waiting to punch you in the face.

return data as User;

}

async function initDashboard() {

try {

const user = await fetchUserData(123);

// CRASH: user.roles is undefined because the API changed to 'roleList'

console.log(user.roles.map(r => r.toUpperCase()));

} catch (e) {

console.error("Well, that didn't work", e);

}

}I spent an hour assuming my logic inside map was wrong. I was stepping through the loop, checking variables. But the issue was upstream. The API response had changed from roles to roleList, but my TypeScript interface didn’t know that.

The fix isn’t better debugging—it’s defensive coding (which makes debugging easier). I started using Zod for runtime validation, but if you don’t want a library, write a type guard. It forces you to inspect the data structure before the crash happens.

Debugging DOM interactions

DOM manipulation in TypeScript is another area where I see people just slap as HTMLElement on everything to shut the compiler up. I’m guilty of this too when I’m prototyping. “I know the button is there,” I say. Then the layout changes.

Here’s a scenario I dealt with regarding a dynamic list. I needed to attach event listeners to items that didn’t exist yet.

// The fragile way

const list = document.getElementById('user-list') as HTMLUListElement;

// If 'user-list' is missing, this variable is null,

// but TS thinks it's an HTMLUListElement.

// Next line throws: Cannot read properties of null (reading 'addEventListener')

list.addEventListener('click', (e) => {

// ...

});When debugging this, don’t just check if list is null. Check what it actually is. Sometimes you grab a div by mistake when you wanted the ul inside it. The debugger’s “Watch” window is your best friend here. Add document.getElementById('user-list') to the watch list and see what it returns live as you step through.

A better approach that saves you debugging time later:

function setupListListener() {

const list = document.getElementById('user-list');

// Explicit check. If this fails, we know exactly why.

if (!list || !(list instanceof HTMLUListElement)) {

console.warn("DOM Element 'user-list' missing or wrong type");

return;

}

// Now TS knows 'list' is definitely HTMLUListElement

list.addEventListener('click', (event) => {

const target = event.target as HTMLElement;

console.log(Clicked on: ${target.tagName});

});

}The “Any” Silencer

We need to talk about any. It’s the “mute” button for your fire alarm.

I was reviewing some code recently where a developer couldn’t figure out why a string method was failing. The variable was typed as any. It turned out to be a number. The debugger showed 42. The code expected "42".

If you find yourself stuck debugging a variable that behaves weirdly, check its definition. If you see any, change it to unknown immediately. TypeScript will force you to write checks to narrow the type, which usually reveals the bug instantly.

Conditional Breakpoints are underrated

If you’re debugging a loop that runs 500 times and fails on iteration 437, do not hit “Continue” 436 times. I watched a junior dev do this once and I almost cried for them.

Right-click your breakpoint in VS Code. Select “Edit Breakpoint”.

// Expression

user.id === 437Now the debugger sleeps until the chaos actually starts. It’s a simple trick, but it saves hours.

Final thought

Debugging TypeScript is mostly about verifying your assumptions. The compiler checks your logic, but it can’t check your data sources or your DOM environment. The bugs that take the longest to solve are almost always the ones where you’re convinced the type definition is true, but the runtime object is something completely different.

So, trust the compiler, but verify with the debugger.