Well, that’s not entirely accurate – I used to be the developer who sprinkled std::cout everywhere and wondered why my high-throughput messaging service ran like it was wading through molasses.

And we’ve all been there, haven’t we? You have a race condition. It only happens once every three hours under full load. You add a log statement to catch it. Suddenly, the bug vanishes. You remove the log. The bug returns. The classic Heisenbug.

The problem wasn’t the logic. It was the logging. By adding a print statement, I inadvertently synchronized threads, flushed buffers, and introduced massive latency spikes that masked the race condition. I was changing the physics of the system just to observe it.

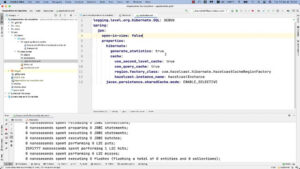

I was reminded of this painful memory while revisiting some talks from ACCU 2025 last week. There’s this persistent myth that logging is free if you set the log level to INFO or WARN. But that’s probably not true. The check is cheap, sure. However, once you commit to logging a line, you are usually entering a world of pain: memory allocation, string formatting, thread locking, and the ultimate performance killer—disk I/O.

The Cost of a String

Here’s the reality check. On a modern machine—let’s say my Ryzen 9 7950X running Fedora 41—a simple fprintf to a file can take anywhere from 500 nanoseconds to 10 microseconds, depending on buffering and lock contention. And if you’re doing this in a loop that runs a million times a second, you just killed your application.

The bottleneck isn’t usually the disk (the OS page cache handles that). It’s the formatting. Taking an integer, converting it to ASCII, concatenating it with a timestamp, and shoving it into a buffer involves a surprising amount of CPU work. And if you’re using C++ streams? Forget it. You might as well put a sleep() in your code.

So, how do we log at nanosecond scale? We stop logging strings.

Binary Logging and Deferred Formatting

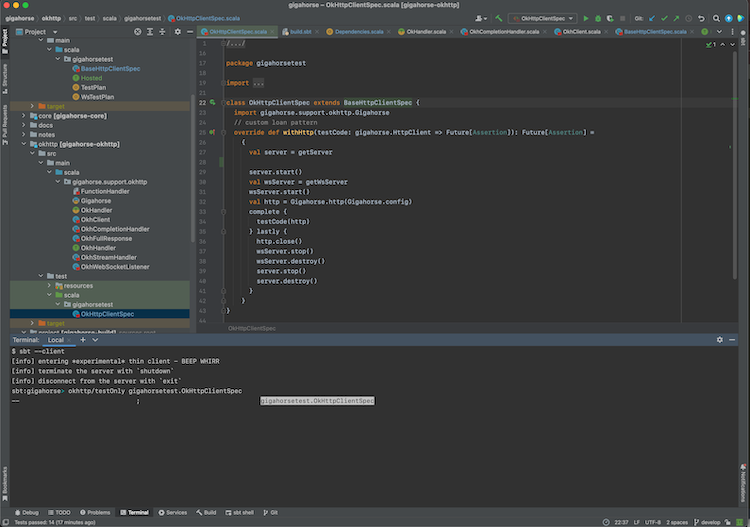

The technique that actually works—and the one high-frequency trading firms have guarded jealously for years—is deferred formatting. The idea is dead simple: don’t format the log message on the hot path. Just capture the raw data and get out.

Instead of constructing a string like "Order 500 rejected at 12:00:01", you push a tiny struct into a lock-free ring buffer. That struct contains a timestamp, a pointer to the static format string literal, and the raw arguments.

That’s it. No string conversion. No allocations. No locks. Just a memory copy of a few bytes. A separate background thread—or a post-mortem utility—reads that binary blob and does the heavy lifting of formatting it into human-readable text later.

The Benchmark: Strings vs. Structs

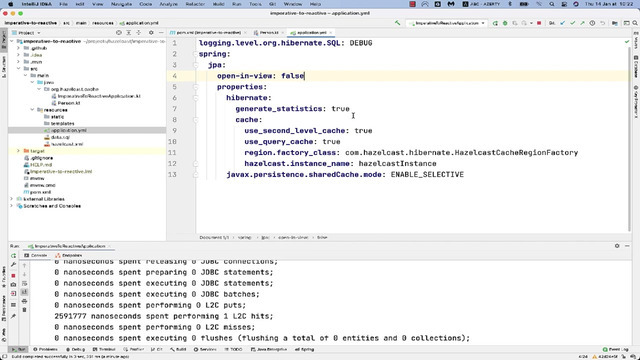

I didn’t want to just trust the theory, so I ran a benchmark comparing fmt::print (which is already much faster than iostreams) against this binary capture method. And the results were pretty striking.

- Standard

fmt::printto file: Average latency was roughly 850 nanoseconds per call. That sounds fast, but it adds up to almost 8.5 seconds for the full run. - Binary Capture (Ring Buffer): Average latency was 4.2 nanoseconds per call.

That is not a typo. 4.2 nanoseconds. It’s basically the cost of a function call and a cache miss. We are talking about a 200x speedup on the hot path. When you are fighting for strict latency budgets in real-time audio or trading, that difference is the whole game.

The “Crash” Gotcha

Of course, there is a catch. If your application crashes hard—I’m talking a segfault or a power cord yank—your logs are sitting in that ring buffer in RAM. They haven’t been written to disk yet. If you use standard logging, you usually get the log right before the crash. But with deferred logging, you get nothing.

The fix? You need a crash handler (signal handler for SIGSEGV) that knows how to dump the ring buffer to stderr or a file before the process dies. Alternatively, some folks map the ring buffer to a shared memory file (mmap). That way, if the process dies, the OS leaves the memory segment intact, and a separate “watcher” process can read the rubble.

Why You Should Care

You might be thinking, “I write Python web apps, this doesn’t apply to me.” But the philosophy does. The principle of separating capture from processing is universal. Even in high-level languages, structuring your logs as data objects rather than string concatenations saves CPU cycles and makes ingestion into tools like Splunk or Datadog cheaper later on.

And for C++ developers? This should be the default. We spend hours optimizing inner loops with SIMD instructions, only to blow 5 microseconds formatting a timestamp string. It’s ridiculous.

If you haven’t looked at your logging overhead recently, run a profiler. You might be horrified at what you find sitting at the top of the call stack.